Clean Plate Club

When Mary Jo Morris (Dining Services) got a bee in her bonnet about implementing a new system that could potentially eliminate food lost to the landfill, that bee kept buzzing and buzzing. Right up until the point when she left her boss’s office with a “yes” in her hand.

Ruth Johnson (Auxiliary Services) oversees food service at the college, and she had just okayed her director’s proposal. “How are you going to pay for it,” she’d asked Morris. And Morris had said, “from the food dollars we will save by eliminating waste.”

And now, leaving Johnson’s office, she swallowed hard and almost backtracked. “Will we really be able to do it?” she wondered.

The cost wasn’t the only hurdle between Morris and her ultimate goal: zero food-waste. In the food industry, that is generally taken to mean less than 10 percent waste sent to the landfill. She still had to present the concept to her kitchen, dining and dish-room staffs. And for that step, Morris chose not to start with the budget issue, or the waste issue, or the extra steps entailed in the system she was proposing. She started, instead, with a screening for the staff of “Trashed,” the award-winning environmental documentary presented by Jeremy Irons.

It wasn’t hard to get engagement from the team, says Morris: “They take out the garbage.” Managers had already been hearing concerns from their own staff – many of them leisure-time gardeners, composters, shoppers and family cooks, after all – about the amount of food wasted.

The new system meant embracing change in big and small ways, from trimming vegetables closer for vegetable broth to building the sorting and weighing of food-waste into habitual patterns. A key component was the introduction of the LeanPath system for monitoring food losses in commercial operations and providing analytics.

“Anything you measure, you can affect,” says Morris. “But you have to start measuring.”

When management launches an initiative, skepticism usually follows. But according to purchaser Cheryl Smits, “The comfort zone was probably set when M.J. said, I don’t care how much we waste at this point in time. We just need to know.” The LeanPath system could give them the detailed, timely information they would need to begin their campaign.

When it comes to implementing change, says Morris, you’ve got to take time. “LeanPath was wonderful at giving us the answer, which was, go slowly. Don’t be punitive. You have to reward people for using the system you introduced.

“We put together presentations; a PowerPoint that spoke about waste. We played the ‘Trashed’ video. We showed them why we should do this; how important this is to the environment. Everybody can buy into that. We brought in a trainer for the whole day.

“I didn’t want the managers to drop too much until they had taken the pulse of the staff. I certainly didn’t want anyone saying, ‘I don’t know why we’re doing this. But M.J. wants it … .’ It comes down to knowing your audience, selling your initiative up front and taking baby steps along the way.”

Chef Dan Froelich was one of the management team that visited other schools using the system. “We went to Michigan Tech and were really impressed. But at one other institution, we met an employee who said, ‘Yeah, we have the system. It just sits on the counter.’ They didn’t do the upfront work we did with LeanPath to prepare everybody.”

Now, at St. Norbert, it’s intuitive at every level. As Morris says, “It’s just the way we work.”

Froelich says one of the first fears people had was, “Am I going to have time to do this?” The system requires weighing each container of discarded foodstuff and entering it on a computerized scale, with the average transaction taking 5-10 seconds. “We really kept talking about that, and that eased their mind a little bit. But when they were able to be trained by one of LeanPath’s people and saw how easy it was … well, now it’s second nature.”

For Froelich, the biggest benefit of the system is the immediacy of it. Before, staff would report food losses in writing and he might not look at the report for weeks. “Now I see the visual. Let’s say we threw out four pans of grilled-cheese sandwiches. Why have I got four pans of grilled cheese left? I go back and find out what happened.”

The analytics were a key factor. Morris says, “We look, we rationalize what happened, we go back to the team: ‘This is what the data’s showing us; what ideas do you have?’ ”

To minimize loss, the crews first pay attention to purchasing and preparation. Through batch-cooking and just-in-time preparation, they have the flexibility to respond to shifting demand.

Froelich says the dining-room staff has become very good at comparing the projection for lunch with the foot-traffic and sending word back when it’s time to make some more of an unexpectedly popular dish. In the kitchen, the pieces and parts of a chicken casserole have been prepared separately for assembly just before serving. Any unused chicken can be frozen for use in another dish; sauce can also be frozen; and the fresh vegetables can be used the next day. “Next time that recipe comes around on the menu,” says Smits, “we can start with what’s on hand.”

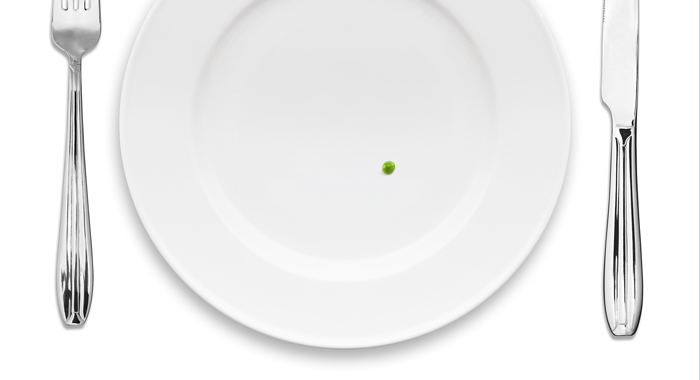

Before food waste was so clearly on the radar of every member of the staff, says Morris, when there were 20 lbs. of casserole left and no menu to slide it into, it went in the garbage. It just wasn’t on the horizon.

“We’re not going to let our quality suffer,” says Froelich. “And the rule of thumb is that we don’t run out,” adds Smits. “The student who arrives for lunch at 1:55 p.m. is paying for the same service as the student who came in at 11 a.m.”

Under the new system, different chef supervisors are responsible for well-organized coolers in which staff can find that freshly made vegetable broth and other delicious beginnings of upcoming menus. Smits has masterminded this effort – the sophisticated commercial equivalent of standing in front of the open refrigerator at home, wondering what to make for supper. As Morris says, “Now we use it; then we threw it.”

It needs a chef’s eye to see what can and cannot be used, Smits says. Theirs is a dynamic menu that has to follow standardized recipes and procedures. But it’s one that still leaves the chefs a lot of flexibility.

The new system wasn’t adopted without a few surprises. Staff found they were ordering fewer garbage bags, for instance, but needing more pans for prepped food; even a new cooler went onto the shopping list.

Froelich says, “I’m really proud of how much waste we have eliminated. We’ve been going from 2,700 lbs. a week to 1,200 lbs. to 1,100 lbs. ... A lot of that has come through menu forecasting. We have a four-week cycle that runs four times through the semester. Once you see what the students are eating, and how much they’re eating, you can start reducing quantities accordingly. LeanPath helps with that, also. But there are just so many new ways people are thinking now, compared with before.”

March 14, 2016