Personally Speaking/Exile in a Dubious Paradise

One year ago I was standing on the beach in Kourou, French Guiana, across from the base of the Troisième Régiment Étranger d’Infanterie (Foreign Legion), where I was staying courtesy of an old college chum. The sun was setting but it was still possible to make out the silhouette of the Salvation Islands, 15 nautical miles off the South American coast. I had made the nine-hour flight from Paris, where I was spending my sabbatical, to visit the most notorious of these former penal colonies: Devil’s Island.

This was an emotional moment for me. The island where I now stood was once the solitary prison-in-exile of Capt. Alfred Dreyfus who, in 1894, was falsely convicted of high treason. A project of my own that had begun as a chapter in a two-volume tome on committed French intellectuals had become a book in its own right, dealing with the officer’s struggle for justice in an affair that shook all of France. For more than a decade, friends and foes of the unfortunate Dreyfus did battle before justice finally prevailed. In 1899, Dreyfus received an official pardon but was not rehabilitated until 1906.

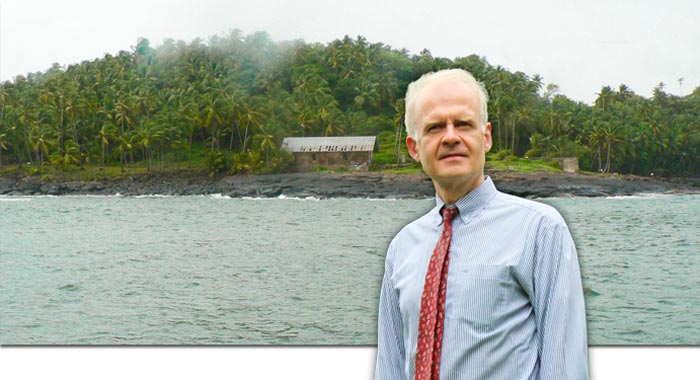

Devil’s Island is the smallest of the three volcanic islands that make up the Salvation Islands and has an area of only 34.6 acres. When France established the Kourou Space Center in French Guiana during the 1960s and sent the Foreign Legion to guard it, the fortunes of the outpost suddenly improved. The government took over Devil’s Island and, in the process of installing remote cameras to monitor rocket flight paths, someone also decided to restore Dreyfus’s cabin. The island has since been closed to ordinary tourists but visitors who pass by at sea can catch a glimpse of this forlorn hut. There is nothing much else to see. Dreyfus’s “bench” is still there, though: some rough stones, 100 feet or so above the majestic sea below, that the prisoner had assembled into a makeshift seat. There, he was allowed to while away his time, dreaming of faraway France.

Naturally, rumors abound about the true purpose of the government installations on this minuscule island and include the preposterous theory that medical experiments are being conducted on monkeys. When I visited Devil’s Island, I was reminded of James Bond in “Dr. No.” Imagine swimming there and being greeted by Ursula Andress! Instead I arrived with a burly légionnaire escort in khaki shorts who made sure I did not take any pictures.

The climate in the Salvation Islands actually is much more pleasant than elsewhere in French Guiana, thanks to the gentle trade winds that helped reduce the presence of infectious diseases and improved prisoners’ chances of survival. The strong sunlight enhances the natural colors of the islands: the overpowering green foliage, the mighty blue ocean, the black volcanic rock. The palm and coconut trees add an exotic touch, and breathtaking views of the water do their part, too, to create an idyllic ambiance.

By 1948, the warders’ mess on the neighboring Île Royale had been transformed into an inn. Today this facility boasts several dozen air-conditioned rooms for less than 100 euros a night. The camp church, decorated by a former inmate-cum-artist, has also been restored and attracts couples from metropolitan France. Visitors can relax on the patio, enjoy an apéritif and watch children at play where the guillotine once stood – its cement supports in the ground still firmly in place. The position of head executioner was much sought after by inmates, and small wonder: he did not have to work, lived in his own quarters, and received the princely sum of 100 francs per head. One famous executioner fancied himself a poet, and excerpts from his oeuvre are available in the hotel bookshop. However, poetry could not save this sensitive brute from the guillotine, and one day he, too, was sentenced to death and quickly dispatched by a newly appointed bourreau.

The business card of my boat rental company eloquently proclaims: “What yesterday was Hell … today is a paradise.” I came and I saw, but part of me felt ashamed that I, too, had let myself be carried away by the mystique of the place.

At a certain point during my two-day odyssey in the footsteps of Captain Dreyfus, I felt saturated and started to question the charm of vacationing in a former penal colony. I saw little effort made to celebrate the life of a significant figure in French history who deserves to be remembered as both a hero and a martyr. The natural beauty of the islands is striking, but real people lived and, more often than not, died here, in horrible circumstances. At what point does the penchant for the bizarre and outlandish in “theme tourism” become obscene? I realize that the whole world cannot become a museum to past injustices. Preserving the horrors of the past should be for the primary purpose of educating future generations, but is not incompatible with responsible tourism.

Tom Conner, professor of modern languages and literatures, was born and raised in Sweden but educated in France and in the United States. He joined the St. Norbert faculty in 1987. His latest book, “The Dreyfus Affair and the Rise of the French Intellectual, 1898-1914,” will be published by McFarland this fall.

Tom Conner, professor of modern languages and literatures, was born and raised in Sweden but educated in France and in the United States. He joined the St. Norbert faculty in 1987. His latest book, “The Dreyfus Affair and the Rise of the French Intellectual, 1898-1914,” will be published by McFarland this fall.July 2, 2013