Land Scouts

Katie Ries (Art) says, “Part of the power of art is shaping culture, and I hope that’s what I’m doing with this.”

Katie Ries (Art) says, “Part of the power of art is shaping culture, and I hope that’s what I’m doing with this.”

Ries is talking about Land Scouts, a project that first began in 2010 while she was a graduate student at the University of Tennessee Knoxville. Now entering her third year as a member of the St. Norbert College faculty, this work-in-progress has traveled along with her and found a whole new home in northeast Wisconsin.

Out of a spirit that seeks to encourage environmentalism in a welcoming manner, Ries says that, as she dreamed up and designed the program, she intentionally steered clear of a type of moralizing that can be so off-putting. “I wanted to bring people to the table in a way that didn’t make them feel like they weren’t doing enough,” she says, “like making their own toilet paper or riding their bike to grandma’s house at Christmas and that sort of stuff.”

The result of all those early efforts has since developed into an educational experience that teaches stewardship so that participants can learn to engage with and take care of their surroundings. The core values are represented by a variety of badges (created by a company in Woodstock, N.Y.) that all serve as symbols representing more complex ideas. They are also outward/visual signs of what is taking place internally.

Although the majority can be taken on in any order, it’s the Observation badge that serves as the required starting point because, as Ries explains, everything begins with noticing and seeing. “Oftentimes, beginners draw what they think they know rather than what they see, so learning to draw is actually a function of learning to see,” she says. “I think learning to see is about learning to recognize patterns and relationships, and I find that very exciting.”

Participants fill field books with drawings and written observations, with a focus on quantity over quality. They enter into the world, pause, and return to reflect. That reflection is intended to lay the groundwork for a more nuanced understanding of the elements that contribute to ecology and environmental preservation.

From there, scouts have the freedom to take on the rest of the badges in any order they choose. The common thread that unites them? “They all require an intimacy and awareness of one’s own land,” says Ries.

Practical beauty

A grant from St. Norbert’s office of faculty development allowed Ries the opportunity to produce the first edition of the Land Scouts Guide Book, which introduces the group, discusses the observation badge and explains how to host a troop.

“I wanted to produce a beautiful object,” she says. “I am an artist and I make things, so I have a real appreciation for that. And I wanted to create media that supports the project so people could hold that book in hand and get excited about it.”

In addition to the hard-copy versions on sale for $25, Ries also wanted to make online PDF versions available for free. “I would like to see this shared widely,” she says. “I don’t want this to be precious or proprietary. I want it to be out in the world.”

The badges will provide inspiration for additional handbooks still to come, she notes. Among the 10 are a variety of intriguing topics including Decomposition, where earning the badge equates to making and maintaining a worm bin. “It’s kind of like a souped-up version of composting,” Ries says: Worms accelerate the decomposition process.

In the same way that observation can be a foundation for understanding complicated ideas, Ries hopes that caring for living creatures can help develop empathy. It also serves as a metaphor, in a way, demonstrating that everyone can do their own small part.

When she visited St. Norbert colleague Nancy Mathias (Sturzl Center) and took a peek in her basement, Ries unearthed one noteworthy model for the process. “Nancy’s bin is just really elegant and high-functioning,” she says. “If you are interested in worms, you should check it out. It is like the Cadillac of worm bins.” Ries was so impressed, in fact, that she took photos in order to use Mathias’s worm bin as a diagram in her next handbook.

Laying the groundwork

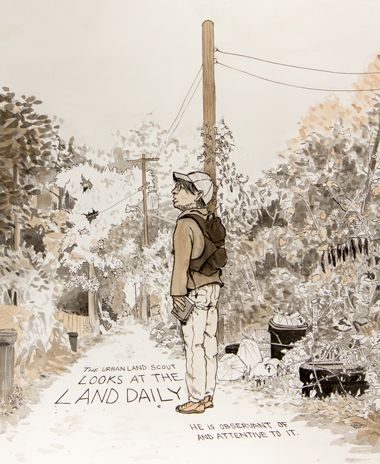

The project has seen a number of changes along the way as Ries has put her ideas into practice. Initially the movement was dubbed Urban Land Scouts, but the Urban has since been dropped in an effort to make it even more inclusive.

And although she began with young, urban people much like herself in mind – those who wanted to do right but weren’t quite ready to become urban homesteaders – she was surprised by the number of parents who were drawn to her initiative and wanted to find out how to get their own kids involved.

As a result, she changed gears and reoriented the program to better serve the middle-school population, and at this point she says students in grades four through six are the ideal fit because their literacy level and earnestness align particularly well.

Ries admits that she’s still exploring and trying new ideas on for size. She has previously held solo workshops for adults and families, and she also held two five-day camps in Knoxville and Nashville that were offered free of charge, thanks to financial support.

“The day camps were fun, just seeing kids geek out about compasses or worms or whatever,” she says. “That was also great in terms of working with these already established community gardens that had tremendous resources in terms of their land, but maybe didn’t have the programmatic structure to do fun, educational stuff for young people.”

One of her goals looking ahead is to introduce similar opportunities for youth in Wisconsin. “My mother is an artist, and I think her encouragement gave me confidence to use art as a tool beyond its decorative value,” Ries explains. “We grew up with gardens and doing outdoorsy things, and I think having a foundation of positive experiences in my own childhood kind of laid the groundwork.”

One of the aspects she most enjoys about Land Scouts is bringing people together and exposing them to a world that awaits right in their own backyard. “What I want to create for people is a positive experience with the natural world,” she adds, “so that they can decide how it fits into their life.”

Accessible by design

Ries is sowing plenty of ideas that she hopes to see come to fruition. She’d like to bring Land Scouts to campus, for instance. This fall, for example, she intends to host a vermicomposting workshop, and working with the students who run the college’s community garden holds plenty of promise as well.

She has also been in conversation with potential partners such as the Hungry Turtle Farm & Learning Center – a new nonprofit focused on sustainable agriculture and community located in Amery, Wis. – and she sees the value of teaming up with fellow faculty members.

As is, Land Scouts is flora-based, but there’s potential to interact with land stewardship more holistically. Issues such as water quality or the handling of material goods like electronic waste, for example, could be explored. The scope could be expanded so that participants who graduate from Land Scouts could move on to Water Scouts or Air Scouts.

Carrie Kissman (Biology) works on the remediation of polluted water bodies, Ries notes as an example. “If we could somehow, with Water Scouts, lay a foundation that supports an understanding of what she’s doing, that would be great,” she says.

“I think there’s a real hunger for this kind of knowledge,” Ries says, “and, like a lot of things, you can read about it online or you can find books about it, but there’s no substitute for having it taught face-to-face, and the transition of knowledge that way. It also becomes social and cultural at the same time. It’s just really exciting for me to see people get excited about this information and take it back to their homes and share it with other people.”

For those who take an interest in what Ries has started, the good news is that she’s designed the program to be as accessible as possible. There’s no need to register or pay, and although projects can be initiated by a troop it’s also easy to get involved on an individual level.

Really, it all boils down to one simple step, she says: "You say the pledge, and you start.”

The Land Scouts’ Pledge

I will, to the best of my ability, be a good steward of the land where I live: by cultivating native and edible plants; promoting species diversity;sharing the fruits of my labor and knowledge; and propagating Land Scouting in barren lands.

Oct. 31, 2015