The Inside Story

Anindo Choudhury (Biology) is smitten.You can hear in his voice and see in his eyes that his is no ordinary love. It’s a passion he self-deprecatingly describes as greedy.The objects of Choudhury’s affection have graceful curves and elegant features that he’s captured in dozens, maybe hundreds, of photographs. Just say the word and he’ll jump to share them.

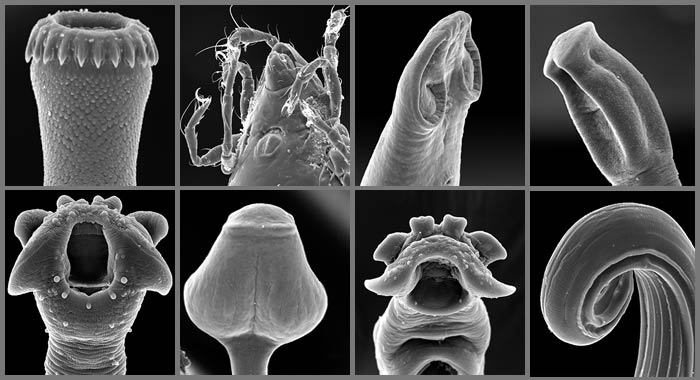

“Aren’t they beautiful?” Choudhury says, scrolling through a few of the photos on his computer.

He points to a particularly lovely specimen and adds, “It looks like a vase.” He pronounces that last word with the sophisticated “ah” befitting an objet d’art.

The objet in question? An Asian fish tapeworm, viewed up close and personal with a scanning electron microscope that sees topographical detail on the micron level.

The images are indeed beautiful in their own way. But for Choudhury, the beauty of fish parasites is more than topography-deep.

“The beauty also comes from the fascination with the way they live,” he says. “The point of parasitism is to be invisible,to thrive and flourish without being noticed. It’s a very delicate game – a dance, a duet – that’s going on between the host and the parasite.”

So far, he’s spent nearly two decades studying that dance from many angles, and in many creatures. His subjects have included flatworms, flukes, tapeworms and spiny-headed worms, but roundworms “remain my first love,” Choudhury says.

Choudhury has collaborated with parasitologists from Mexico to Manitoba and California to the Czech Republic to understand the myriad factors that make parasitic relationships work. “The overarching question that I’m interested in is, why do certain parasites belong with certain hosts? Why are they together, in space and in time? Why are they together now, and how did they come to be together? In order to answer those questions, you have to go beyond just one type of research.”

He’s certainly done that. During his career, he has rafted the Little Colorado River with National Wildlife Health Center parasitologist Rebecca Cole to explore the effect of changing river temperatures on the distribution of the Asian fish tapeworm; taken undergraduates to Panama in further pursuit of the same parasite; collaborated with other students to name new Wisconsin tapeworm species; and served as associate editor of the Journal of Parasitology, one of the field’s top three journals worldwide. And it all began with interests that took hold in boyhood and didn’t let go.

As a young child, Choudhury moved from his Austrian mother’s homeland to his father’s native India. On his walk to school, he recalls seeing people with hugely swollen legs. When he asked his mother about them, she explained elephantiasis and its cause – the transmission of parasitic filaria larva to humans by mosquitos. He was fascinated.

A few years later, his father taught him to fish, and he fell in love with angling and all things fish-related. Eventually, his dual interests came together.

He got a bachelor’s degree in zoology at the University of Burdwan in India and a master’s in marine parasitology at the University of New Brunswick. Then a portion of Choudhury’s doctoral research at the University of Manitoba established a connection to northeast Wisconsin long before he came to live there.

Choudhury studied the parasites of Lake Winnebago sturgeon when Lake Winnebago was little more to him than a sizable blue oval on a map. The sturgeon used in his research were frozen and shipped to him by Ron Bruch, a Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources sturgeon expert.

“I actually named a parasite after him. It’s a fluke found in sturgeon in Wisconsin,” Choudhury says.

This is high praise from a parasitologist. A Brazilian post-doctoral colleague of Choudhury’s similarly honored him, naming a new stingray tapeworm genus Anindobothriumin a nod to what may be Choudhury’s boldest experiment.

At work late one night, Choudhury, then a doctoral student in Manitoba, discovered live larvae in the flesh of pike harvested from a remote Canadian lake. Studying the larvae under a microscope, he believed them to be Diphyllobothrium latum, the human broad tapeworm.

While every parasitologist is familiar with D. latum,a parasitic rock star used to illustrate the tapeworm life cycle in both introductory and advanced textbooks, few have ever seen it live. And this human-borne parasite certainly didn’t belong in an uninhabited Canadian wilderness. Could the larvae really be D. latum?

Absent the molecular tools he needed to answer the question, there was only one way for Choudhury to find out: give the larval parasite a human home in which to grow up.

The next day Choudhury swallowed three small chunks of raw, larvae-infested pike with chocolate milk. “Tapeworms love sugar,” Choudhury says. “I wanted to make the transition comfortable for them. I had to give them a head start.”

Choudhury’s TLC did the trick. For five years, the parasite thrived in his gut. He collected specimens periodically, preserved them in 100 percent ethanol and, years later, collaborated with St. Norbert undergraduates to study the samples’ molecular genetics.

While not all of his collaborative projects with students are as personal as this one, he relishes his work with undergraduates. “I wish instead of writing about me you could write about all of the students I’ve had,” he says. “It’s why I came here. I wanted to engage these bright young minds in something I’m really passionate about and I enjoy. Don’t you think it’s much more fun if you enjoy something with somebody rather than by yourself? It’s infectious. My excitement and passion rub off on them, and theirs rub off on me. We just feed off one another.”

Nov. 19, 2013