Geology Alum Has Front-Row Seat as Perseverance Rover Findings Are Unveiled

Geologist Sara Schreder-Gomes ’19 has a front-row seat as the findings of NASA’s Perseverance rover are unveiled. Schreder-Gomes is finishing a master’s program at the University of West Virginia during which her thesis advisor was selected by NASA as a return-sample selection participating scientist.

Geologist Sara Schreder-Gomes ’19 has a front-row seat as the findings of NASA’s Perseverance rover are unveiled. Schreder-Gomes is finishing a master’s program at the University of West Virginia during which her thesis advisor was selected by NASA as a return-sample selection participating scientist.

Schreder-Gomes (left) was attracted to the UWV program because her advisor, Kathleen Benison, had just received a two-year NASA astrobiology grant to study modern and fossil microorganisms trapped in halite and gypsum salt lakes, in order to refine methods for evaluating evidence for past life on Mars and other bodies in the solar system. The possible future applications are even more exciting than the Krispy Kreme Mars donut created to celebrate the February landing of Perseverance.

“This is what I love about geology, that we can take what we know about Earth systems and apply it to other planets,” Schreder-Gomes says. “I love the stories we can learn from rocks, about what happened to the Earth in deep time, and we are living in such exciting times in terms of how we can use that knowledge. Dr Benison has shared what she has been learning so we’ve all had this unique opportunity.

“We use a concept called comparative sedimentology; this simply means that we study modern systems to infer things about similar systems in the past. We can do the same thing when learning about Mars: by studying certain times or conditions in Earth’s history, we can learn about Mars.”

Her own research is on fluid inclusions (tiny trapped water globules) in 830 million-year-old salt deposits from central Australia. “We think the area this salt comes from was deposited in an area that had a series of hyper saline lakes, up to 10 times saltier than seawater, similar to those in Death Valley [a practice site for Perseverance].

“During this time the only life on Earth was microorganisms and some of these were contained in fluid inclusions, the tiny bits of water that get trapped as salt is growing. So the fluid inclusions are a snapshot of the past. They can tell us a lot about the surface waters the salt grew in (like salinity and water chemistry, atmospheric conditions at the time it was growing), and now we’re learning about how they can tell us about the microscopic life in those ancient waters, which won’t have altered since the rocks were formed.

“There’s a lot of evidence that microorganisms can survive (still be alive) in fluid inclusions for up to 250 million years. This, plus my research that’s able to recognize them in rocks after 830 million years, gives us a lot of hope that we would be able to find evidence of life in similar rocks on Mars.”

Schreder-Gomes found her niche in geology by accident. “When I applied to St. Norbert, I hadn’t decided on my major and they paired me with a geology major who showed me around: we’re still friends. I came to realize that geologists are all kinds of scientists – chemists, physicists and biologists – but we do it in our own way.

“My training as a geologist at SNC prepared me well for graduate school. I was a first-generation college student and the mentoring I was given made it possible to do what I do now. I was taught how to make detailed observations and interpret them within a wider context.”

She was led towards her research in ancient rocks by studies in the St. Norbert fossil prep lab with Rebecca McKean ’04 (Geology), where McKean and her students are Unpacking a Plesiosaur.

“I’m a sedimentologist, not a paleontologist, but as I’m studying microorganisms – which are microfossils – I am thinking like a paleontologist too. I am looking for biosignatures, which is one of the goals of the NASA rover program.”

She is also grateful for the ample field experiences at St. Norbert. “Our professors really put in the extra effort to make sure we got this – something that has stuck with me through the years is professor of geology Tim Flood saying that we should never pass up an opportunity to go in the field or look at samples, because ‘the difference between a good geologist and a great geologist is that a great geologist has seen more rocks.’ ”

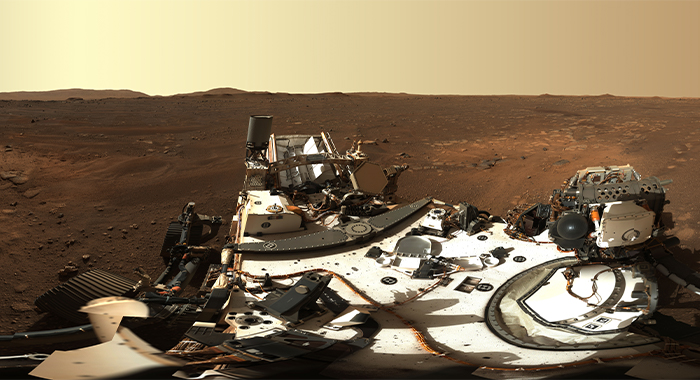

Now she has had a chance to observe the unique challenges of fieldwork with NASA’s virtual field assistant (Percy) as Benison and other return sample scientists tackled the huge responsibility of deciding where to take samples and how many to take at various locations on the rover’s path in and around Jezero Crater. (Jezero was chosen because the crater is believed to have once held a longstanding lake.)

“As geologists we’re trained to hold rocks in our hands; it’s much more challenging to look at pictures even if they can still provide a wealth of knowledge. You’re only able to see what’s on the surface. Geologists are also used to taking lots of samples in the field. You might have a backpack of rocks the size of a tennis ball. But the Rover samples are more like the size of a pea or a piece of chalk, and limited in number and you can’t pick a sample up and then put it back if you find a better one. You have to stick with your choices.”

With the end of her masters program in sight, Schreder-Gomes is writing up her findings and plans to head back to Wisconsin to be near family and work in industry. Her only slight regret has been missing her lab buddies under pandemic conditions. “I’ve been able to go into the lab for a just a few hours at a time and been the only person there. I miss the camaraderie of the lab – there’s nothing like calling your colleagues over to see something exciting you’ve found, it’s not the same sharing your screen on Zoom.

“Doing research during a pandemic has been incredibly difficult, but I am constantly inspired by the work I have the privilege of doing.”

March 11, 2021